The Visualisation of News Reports (A Comparative Analysis of Newspapers in Seven Different Countries): Myths, Identities and Culture

Business Meets Art: Beyond the Traditional Approach to Education, management and Business. (2016). RISEBA. ISBN 978-9984-705-32-3

Sandra Veinberg

Abstract

This paper examines the process of visualisation and conducts a test with regard to how the meditations of the media impact various journalistic fields in different countries that issue news reports. In order to analyse this visualisation (as a news phenomenon) I needed to find an event that was interesting for nearly all of the world’s media. I therefore decided to choose the Assange case and made an attempt at analysing the current “global hunt” that is centred around the founder of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange. As my source, I have used a total of 890 published articles from online media sources, covering seven different countries: Sweden, the UK, Ecuador, Russia, Latvia, Malaysia, and Japan. The objective was to observe the visualisation of news reports over the last year and a half (between the start of 2012 and April 2013). The results of my research produced confirmation that the majority of articles revealed evidence of a clear visualisation of the information. My conclusion is that stories involving news reports use the process of visualisation to quickly explain a current situation where it is almost inexplicable. The Assange case has created just such an inexplicable report thanks to WikiLeaks’ publications of classified documents, the varied reaction of society to this publication, and the lengthy legal process that has been put in motion against Julian Assange in the Swedish and British courts. I found that the visualisation of news reports had an effect on the journalistic field from one country to another, but it also had an influence on international relations and diplomacy.

Keywords: visualisation of reports, international relations, public relations, media mediation, culture

Introduction

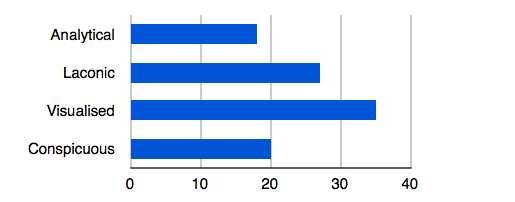

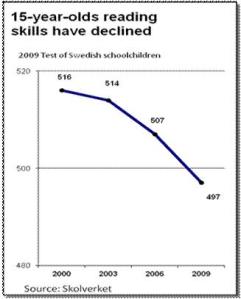

This study involves an analysis of newspaper articles in various journalistic fields that cover the same event. An analysis of the visualisation for these articles shows that reports in newspapers have become shorter and sharper, and that they have a stronger ability to affect the reader emotionally. Much of today’s journalistic field works with similar forms in news journalism: the length of articles today is limited. In cases where an article covers facts that require lengthy explanation, the text tries to help with an “active visualisation”. For examining various points, it may be necessary to begin with: 1) whether there is “the tendency to imitate the effects of visual art” (Mitchell, 2007, p. 94), and 2) how this visualisation is realised in text generally. During the investigation it may be concluded that the journalistic field also affects the social field and was also reflected in both intergovernmental and international relations.

First of all, it might be appropriate to include a brief explanation about the Assange case: Julian Assange is the founder and editor-in-chief of WikiLeaks. He is known for his activities at the self-made organisation known as WikiLeaks, which published a series of confidential documents, most of them from the US. Reactions in the world’s media, diplomatic circles, and in the social sphere to the WikiLeaks publications have been different. There is no doubt that this was a scoop as far as the global public sphere is concerned; therefore, reactions to it have so far been rather strong. The US and its allies consider Assange to be a terrorist. The opposite view is shared by many others, who regard him as a freedom fighter and the digital world’s Robin Hood. Thanks to the publications made through WikiLeaks, he has been chased by opponents from several directions. His situation was at its worst in autumn 2010, when he was interrogated by the police on suspicion of raping two Swedish women. He personally denies any breach of the law. After a long series of trials in Britain, where Assange tried to appeal against extradition to Sweden, he lost the final decision. In order to avoid expulsion from Britain and deportation to Sweden, he demanded and received political asylum in Ecuador. Since then he has resided in Ecuador’s embassy in London without any opportunity to venture out in public. He refuses extradition to Sweden because he believes that the United States may affect the trial processes in Stockholm and may require his forced deportation to America, where he could face the death penalty thanks to his activities at WikiLeaks. Various media outlets in different countries illustrate this case in different ways.

This investigation does not comprise research into the legalities of the matter. It is clear that the complexity of the legal procedures has dramatized the Assange case sharply, transforming a routine investigation in the media world into a scandalous political persecution. The most important aspect here is the conclusion that the media misunderstanding of the complexity of the legal process has confused the international media corps and caused a confrontation in terms of international relations. One can only conclude that Vladimir Putin, Oliver Stone, Fidel Castro, Hugo Chavez, and Rafael Correra welcomed Ecuador’s decision to provide Assange with political asylum, but Sweden’s foreign minister, Carl Bildt, and a number of leading politicians from the UK have condemned this. We can conclude that one and the same event has been interpreted in different ways in different countries through various journalistic fields (Bourdieu, 2005), and because of this it has influenced not only the media coverage in different countries, but also the political, diplomatic and international image in intergovernmental relations.

Background of the Study

Communication is necessary for cultural innovation and human survival. “We live today in an ever- increasingly hyper-interconnected world, a global acumen of communicative interactions and exchanges that stimulates profound cultural transformations and realignments” (Hannerz, 1996, p.33). The most sweeping dimension of communication is connectivity, which is realised via the internet and information technology and which offers incredible social opportunities.

Language and the written text has always been associated with image-making, but rarely has this process become involved in the social sciences, in journalistic research. The Canadian anthropologist Grant McCracken offers the analogy of linguistic structure and uses language to demonstrate the vitality in the routine of social interaction (McCracken, 1990, p.63). It is possible that in the current situation communication shows a slightly different face. It flows across borders and changes itself according to the dominant ideology in each individual country.

Ideologies are internally coherent ways of thinking: “they are points of view that may or may not be “true”; that is, ideologies are not necessarily grounded in historically or empirically verifiable fact” (Lull, 2006, p.13). Organised thought is never innocent. Mass media tends to create “the organised thought” within their country’s borders in synchronisation with the local habitus and the social field. It always serves a purpose. Naturally, mass media and all other large-scale social institutions play a vital role in the dissemination of macro-level ideologies. British sociologist John B Thompson insists that ideology is best understood in the narrower sense of “dominant ideology”, where “symbolic forms”, including language, play a major role. This means that the agenda in the public space is often created by counter-hegemonic messages from media industries, including the news.

The ideologies of mass media play a very influential role in public consciousness. Consciousness is not fixed. It is impermanent and malleable. It is shaped by the media, but also by many other information sources. Conscious information is not always self-evident. “The local ideology” formed by the domestic media in each country on an individual basis is obviously addressed only to “the local reader”. “Just as fish tend not to problematise the water in which they swim, people certainly don’t always analyse how their everyday environments, including media messages, shape their thinking.” (Lull, 2006, p. 29).

If one of a country’s journalistic fields collides with the journalistic field of a foreign country, we can suspect that a cultural conflict is to blame. Culture is a conceptual system which on the surface appears in the words of people’s language (Agar, 1994, p. 79). Anyone who speaks more than one language understands very well that language is much more than just words. We cannot separate language from culture; they are intimately connected through meaning. “Though language may be one surface of culture, personal interpretations and the use of language are by no means superficial; the most profound meanings are fashioned through language. We learn who ‘we’ are, and who ‘they’ are, largely through language.” (Lull, 2006, p. 139). Agar defines culture as “something you make up to fill in the spaces between them and you.” (Agar, 1994, p.128). Language is about differences in the way people live.

As a system of symbols, language is expressed and perceived both as an audio code and as a visual code. Mastering the various modes and codes of communication shows how one becomes part of culture. Like all symbolic forms, language is a resource for social construction and culture. Certainly, one of the most systematic and well-known attempts to come to grips on a theoretical basis with the relationship between culture and social structure is the one that was undertaken by the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. He resurrected and reworked the concept of habitus to bring all of the lifestyle factors into one explanatory paradigm based on situated social interaction. Habitus is how we live and is learned through social experience. Media reflect habitus.

Everyday global news media carries stories that cover events involving foreign governments and their populations. War rather than peace makes the news headlines, and understandably so, because the violent conflict of war so visibly ravages human societies. “‘If it bleeds, it leads’; so goes the cynical media adage.” (Devetak, 2012). Global news by virtual communication today penetrates all barriers (nationally, regionally, and locally) and on the road (through the obstacle course of “noise”) (Fiske, 1998) can create essential changes in the appearance (content) of the message. In this way, the content of the message may no longer correspond to real events that have actually occurred in real life. This creates communicative confusion which may be expressed in international relations. That is to say, a defect in media relations may result which may be reflected in international relations. In the era of globalisation “the scope of diplomacy and public relations becomes broader as technology facilitates communication across national frontiers and creates more publics” (L’Etang, 2006, p. 378).

Methodology

In order to analyse a variety of newspaper reports and compare them by visualising them, we can use various qualitative research methods. My research is based on an analysis of qualitative research (a qualitative study) of 890 newspaper reports by two methods: a critical analysis of visual communication (Bergström, 1998, p. 45), and the fallacy of a “pictorial turn” (Mitchell, 2007, p. 94).

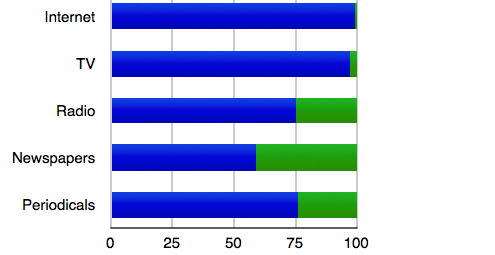

Firstly, all of today’s media is in the form of mixed media. This means that the old “classification” of the media in which all newspapers and magazines were classified as “printed” (text) media and radio and TV were considered as being audio-visual is now an outdated assumption. We can agree with Mitchell, who pointed out that today one “is allowed to say what is true: that literature, insofar as it is written or printed, has an unavoidable visual component which bears a specific relation to an auditory component, which is why it makes a difference whether a novel is read aloud or silently. We are also allowed to notice that literature, in techniques like emphasis and description… involves ‘virtual’ or ‘imaginative’ experiences of space and vision that are no less real for being indirectly conveyed through language” (Mitchell, 2007, p. 95). This means that newspaper reports also now belong to visual culture.

It is important to understand what Mitchell calls “the visual construction of the social field” (2005, p. 345). This can be realised even through internet online media. The visual culture “is not an object-based field, but a cross-cultural, cross-platform, and cross-temporal comparison” (Mirzoeff, 2009, p. 2).

There are three categories in my analysis model: 1) “ten myths”, “eight theses”, and “five constitutive fallacies about visual culture”, from Mitchel (Mitchell, 2007, pp. 90-92.); 2) seven paradoxes and comparisons from Mirzoeff: a) conflicts, b) comparisons, c) sensibility, d) perspective and policy, e) race, f) the fetish, or the gaze, g) celebrity (Mirzoeff, 2009); and finally, 3) three criteria for “good visual communication” by Bergström: intention, ethics and aesthetics (Bergström, 1998, p. 45). It should be noted that this is research about verbal visualisation.

Analysis, Findings, Results

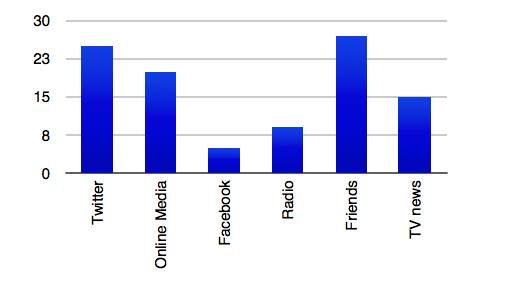

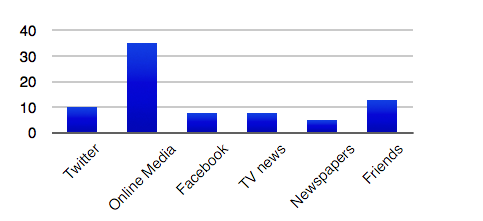

The analysis of news reports included 890 articles from seven different countries. All of the online media publications cover the Assange case. The period over which the analysis was carried out took place during the last two years, covering all of 2012 and extending to April 2013 for Sweden, the UK, Ecuador, Russia, Latvia and Malaysia, and covering 2010 to April 2013 for Japan.

The research results show that the greatest number of articles demonstrates reportage (translations) from the so-called main theatres of action: Stockholm and London.

Sweden first and foremost is the main stage. It was here that criminal charges were brought against Assange and it was here that everything began. Therefore, the Swedish media mention the case most frequently and most intensely. The analysis started with two of the country’s highest quality and largest dailies: the liberal Dagens Nyheter and the liberal-conservative Svenska Dagbladet. Both are published in Swedish. Among English media, the Guardian was selected. At first it was thought that this source should function only as a means of comparison with the information coming out of the Swedish media, but after a review of all 275 British news articles on the Assange case, including from the Guardian, which were published during the time period 2012-2013, it became clear that the British media has control over the agenda. It was decided to compare Swedish and British newspapers with the media from Ecuador, Russia, Latvia, Malaysia and Japan. This means that it was possible to analyse 95 media articles about the Assange case from Latvia (drawing on the newspapers Diena, Neatkarīgā Rīta Avīze, and Latvijas Avīze, all in Latvian); 50 from Russia (Лента, РИО, and Суббота, all in Russian); 23 from Malaysia (the Star, Mysarawak, Borneo Post, and the Asian Correspondent, all in English); fifteen from Ecuador (El Comercio, written in Spanish); and finally 126 from Japan (the Japan Times, written in English).

Upon completion of a review of all of the publications, it was clear that it is only possible to reflect the dominant trends for the visualisation. Therefore, it was decided to quote only the most typical elements and focus on the most visible trends. It is clear that the journalistic field also has certain exceptions that deviate from the dominant norm in each country’s journalism.

Most newspaper reports are visual, and they evoke visual associations. I sorted all the linguistic expressions through a yardstick description: “who is he”.

I forecasted that the visualisation would be strong, and this turned out to be correct. This depends on the emotional attitude in media reports, which is the dominant reflection of the Assange case. Firstly, we can see that the picture is almost only just black or white and is strongly polarised. The media paints him (in textual form) as a “good” or “evil” person, and the colours in the description are full of contrast. Secondly, the media tries to transform coverage of an ordinary trial into a noble battle between good and evil powers (Samson versus Goliath).

First up is Sweden, which predominantly issues a dark picture of Assange. It can be concluded that the Swedish media occupies a defensive position in his rhetoric. We can see a hint of bitterness in reaction to “the very negative image of the Swedish judicial system that has been spread overseas”. In Dagens Nyheter we can observe a strong and consistently negative image of Assange: “he is really sick”, “he is a selfish coward who ignores women”, “he’s a douchebag”, all terms used by the Swedish Minister for Social Affairs, Göran Hägglund” (“Lagen”, 2012). The same direction applies to the other Swedish quality paper, Svenska Dagbladet. It writes that: “This chicken only has a feather left”, which was a comment by Swedish Foreign Minister, Carl Bildt, when responding to the secret documents being issued on WikiLeaks (and when referring to Julian Assange himself) which show that he has been an “informant” for the US (“Bildt”, 2013).

The opposite position can be seen in the Ecuadorian media’s coverage of the Assange case. While the emotional attitude to the description of Assange still dominates, it goes in completely the opposite direction. Ecuador’s El Comercio largely sees the Assange case as a purely political process in which Assange is like a national hero. Most of the material published in El Comercio celebrates Assange and exhibits the fact that: “Hugo Chavez supports Assange,” (“Caso”, 2012) and Fidel Castro is in good health and is thinking the same thing”, while the “UNASUR, which is made up of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Suriname and Uruguay, supports and celebrates Assange” (“Unasur y ALBA”, 2012; “Unasur respalda”, 2012). Almost the same visualisation of the report can be found in Russian newspapers. Here there is less of a political dimension, but a greater element of praise, celebrating Assange as “a good man” (“Dzhulian”, 2012); “Assanzh poobeshchal”, 2012)

The lyrical turn of phrase exercised by Russian newspapers in which Russian journalists describe Julian Assange is usually highly emotional and therefore paints a picture of an “involved journalist”, an “IT specialist who is hunted by foreign enemy powers”, an “Australian programmer”, “the founder of WikiLeaks”, “a political refugee”, “during his childhood he went to 37 different schools”, “liked self-training”, “he adores the exact sciences”, “president of the Australian Institute for Collaborative Research”, a “physicist”, a “good guy”, one of the “two most wanted men”, “the guy who has been locked up” (“Ekvador”, 2012; “Na kavo”, 2012; “Assanzh”, 2013).

Media coverage in Latvia is similar to the example seen in neighbouring Russia. A total of 95 articles in the three major morning newspapers provide information about the Assange case and consider him to be: “the founder of WikiLeaks”, “a popular person”, “an Australian citizen”, “a celebrity”, “desirable”, “someone that the media likes to discredit”, “rich and popular”, “desirable” (again), “attractive”, “charming”, and a “slender, erudite activist” (“WikiLeaks”, 2012; “Asanžs”, 2011; “Mediji”, 2012).

British newspapers offer highly ironic, emotionally fractious, ill-tempered, and little-distanced descriptions of Assange. He is: a “high-profile opponent of Britain’s monarchy” (“Julian”, 2013), “the former computer hacker, and Australian citizen”, “the silver-haired Assange” (“Why is”, 2011), “like Murdoch, born in Australia” (Goodman, 2012); “Assange is acting out melodrama”, is a protagonist in a “political thriller… Greek tragedy… soap opera” (Ball, 2012); “this is a man who, after all, has yet to be charged, let alone convicted, of anything”, and as far as the bulk of the press is concerned, Assange is nothing but a “monstrous narcissist”, a “bail-jumping sex pest”, and an “exhibitionist maniac” (Milne, 2012); “this /Assange case/ is not a policy issue for the Labour party” (Quinn, 2013); “the former computer hacker” (Townsend, 2010) “is a creation of the global right, designed to make the left look ridiculous” (“Please”, 2013); “the man at the centre of controversy – who refused to be gracious” (Greenslade, 2013), the “self-proclaimed defender of truth and freedom” (Elder, 2012) “has sparked intense personal animosity, especially in media circles” (Ball, 2012). We can see the irritation in British publications when it comes to Assange’s residence in the country and his activities in the UK, and newspaper articles create a picture of an unstable person, a narcissistic cheat, a clown.

Malaysian publications show a very considerable degree of influence from the British way of reporting on the Assange case. Their output coincides with British expressions: “WikiLeaks founder” (“WikiLeaks founder”, 2010; “WikiLeaks’ Assange”, 2013), “the former computer hacker” (“Assange embassy”, 2013), “the man behind WikiLeaks” (“WikiLeaks founder”, 2010), “Internet activist”, and “Australian journalist” (“WikiLeaks’ Assange”, 2013). One can even encounter a clean “copy” of some expressions: “the silver-haired Assange” (“A spotlight”, 2010), “the former computer hacker, and Australian” (“Wikileaks founder Assange”, 2012), and “high-profile opponent of Britain’s monarchy” (“Assange appoints”, 2013). This can be explained easily: Malaysian English-language newspapers often reproduce English newspaper articles completely and tend to use British and Australian sources and writers who feed on the English-language media sphere. But the newspapers’ choice of words here (in the description of Assange) are more cautious. We see this most in terms of the use of “a computer hacker” and “WikiLeaks founder”, a paradox that cannot be explained.

The Japan Times examines the Assange case through 125 articles. Most of them have subtitles, using phrases such as “Crime”, “WikiLeaks founder”, “Australian-born founder of the controversial WikiLeaks site” (“WikiLeaks Party”, 2013), “WikiLeaks organiser Julian Assange – the Joker in Christopher Nolan’s movie ‘The Dark Knight’” (“Waiting”, 2011), “behind Assange’s Arrest: Sweden’s Sex-Crime Problem”, “WikiLeaks chief”, “Mr Assange”, “founder-director of WikiLeaks” (“Sexual”, 2010), “WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange” (“Why”, 2013). Even here we can observe that the newspaper reproduces English newspaper articles completely and tends to use sources from the English-language media sphere.

One can also discern a certain number of publications in which the media tries to realise a constructive informative description of Julian Assange (without strong emotional connotations), but most of them have failed thanks to their strong verbal visualisation. The Guardian reports that Julian Assange is actually a busy man: he “wants to be Australia’s senator”, “struck a defiant tone in a recent interview” (“Julian”, 2013), “is under house arrest outside London”, and “will interview noteworthy figures on a show called The World Tomorrow in Russia” (Harding, 2012). The Russian media also provides a broader insight into Assange’s activities here, where it can be observed that Assange, a busy man, has “unveiled a new talk show with his own version of a sensational get”, or that he has “discussed Israel, Lebanon and Syria on a video link”, and “supports the opposition forces in Syria” (“Assanzh raskritikoval”, 2013; “Assanzh, Dzhulian”, 2013; “Britanskiy”, 2011).

Meanwhile, in Dagens Nyheter, even certified, factual information is imbued with emotional rhetoric: “His stay in the UK has cost the British police 38 million SEK” (“Kritik”, 2013), “freedom on bail for him cost 93,500 GBP” (“Amnesty”, 2012; “Assanges”, 2012). These phrases strike a tone of condemnation and the newspaper comes to the conclusion that all of Assange’s actions are ridiculous: “his idea to move into an embassy is absurd” (“Borgström”, 2012). Svenska Dagbladet continues in the same vein: “the WikiLeaks founder has been hiding in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London since June 2012” (“Dags”, 2014). Ecuador’s El Comercio mostly sees the Assange case as a purely political process. It’s mostly about ministerial meetings, when Ecuador granted Assange asylum in the embassy. It’s about political discussions between members of the OAS. In addition, the country’s president, Rafael Correa, acknowledges that “the criminal offences which are under investigation in Sweden would not be crimes here in Ecuador” (“Kryphål”, 2013; Carp, 2012).

In its description of the Assange case, the media cannot find a balance between entropic and redundant information. Because the Assange case is rather complicated, journalists are trying to avoid an entropic accent and paint the obvious, redundant picture of the case. It seems that the media have a hard time visualising the compromise between “the data world’s Robin Hood” and “the violent offender in Sweden”. “Assange replied evasively to questions about rape charges against him and the decision to refuse to allow himself to be extradited to Sweden for questioning” (“Ecuador”, 2013; “Åklagare”, 2014). Dagens Nyheter publications show both surprise and annoyance at the way that Assange has been fighting against being extradited from Great Britain to Sweden.

The Guardian manifests a few awkward situations with entropic elements (without simplification): “To stay in the embassy is no exit for Assange, because Ecuador is a country with a tenuous respect for international human rights law. This is a counter-intuitive refuge for free speech and transparency” (“Julian”, 2012; Ball, 2012). There are also references to the supporters of his activities: “[Oliver Stone] a long- time supporter of Assange” (Child, 2013), “young and old, they [supporters] were there to demonstrate their solidarity with someone whose guts they admired” (Pilger, 2013). The Japan Times tries to immerse itself in the complex (inexplicable) problems experienced by Swedish journalists and experts, during subtitle politicking and diplomacy. In Sweden, Marten Schultz, professor of law at Stockholm University, tries to explain “that Julian Assange, Michael Moore, the feminist Naomi Wolf, the journalist John Pilger, and many others, have launched attacks on the Swedish legal system… the caricature has been allowed to dominate impressions of Sweden, the representatives of its legal system, and other Swedish experts have failed to provide a more accurate picture” (“In Sweden”, 2012). Paulina Neuding wrote here about the cultural contradictions of Europe’s multiculturalism (“The cultural”, 2011) and pointed out that the country is one of the most radical in its understanding of women’s rights, as WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange can attest. It is interesting to note that the Japanese news adds a heavy accent on the problems that the Assange case has caused in terms of intergovernmental relations. This is where we can see Assange as a hindrance, a faceless entity that interferes in international relations between Sweden, the UK, Ecuador, and Russia. Because of this, a plurality of analytical articles have been written under the title “Diplomacy”: “WikiLeaks co-founder Julian Assange has behaved irresponsibly… I thoroughly deplore… the WikiLeaks releases, but we must continue to speak frankly and critically when appropriate” (“When does”, 2010).

The strongest impression is made by Assange´s visualisation as a hero. The “hero status” undoubtedly comes from his work at WikiLeaks. In this regard, the Swedish newspapers have the weakest position when it comes to the visual representation of Assange. They try to devalue Assange’s hero status to the everyday level: “there is no reason to treat Assange differently from other people in this situation. There should be equality before the law” (Kryphål, 2013). For the Guardian there is no doubt that Assange is a hero, and therefore Lady Gaga “dropped by the Ecuadorian embassy to see Julian Assange… stayed with him for five hours” (Booth, 2012); the newspaper points out that Assange is strong – “the truth is I love a good fight. Many people are counting on me to be strong” (“Julian”, 2013) – and intelligent: “has been invited to speak at the 189-year-old Oxford Union debating society” (“Oxford”, 2013). The Russian media has remarked that “he is on the list of the hundred most influential people in the world”, and that he “did everything he could to minimise his prison-like isolation and behaved surprisingly like a standard network interviewer” and “has plans to develop scientific journalism” (“Tupik”, 2012; “Dzhulian”, 2010; “Assanzh poobeshchal”, 2012). A Latvian newspaper conjures up the same image, mentioning that Julian Assange received an award in 2011 from the Serbian Press Association (“Asanžam”, 2011).

The stubborn media blindness in the visualisation of Julian Assange can be seen better when analysing the counterposition to “David versus Goliath”. In this we can see how the journalistic field advances various roles for its heroes. The Swedish media paints a picture of Assange as Goliath while the Swedish state is David. The dramatic triangle looks like this: a) the “sacrifice” here is two women, who are represented by Swedish law; b) “the tracker” is Julian Assange, who does not obey the law; and c) “the rescuer” is the law and the court process. The legal system in Sweden is independent, notes the country’s Foreign Minister, Carl Bildt. Assange’s idea that he is at risk of being deported from Sweden to the United States is, considers the minister, part of “Assange’s fantasy world” (“Kryphål”, 2012; “Wikileaks: Swedish”, 2012), “the WikiLeaks founder is doing what he can to demonise Swedish law” (“Sverige”, 2012).

In the Russian media, the picture is reversed. Here the Assange role is equated with David and the Swedish justice system represents Goliath, something to be fought. The Russian media posits Assange as “the first enemy of the US security forces” (“Velikiy”, 2010). The Russian sources also show the enemy in the form of the two women who brought criminal charges against him in Sweden. Here they are called “the ladies who incriminated our hero,” who “pretend that they have been raped”, and who “agreed to have sex with him, being fully ready themselves to have sex with him” (“Assanzh poobeshchal”, 2012; “Assanzh. Generalny”, 2010); “Assanzh ne sobirayetsya”, 2014; “Obvinayushchiye”, 2010; “Zalech”, 2012). Some newspapers even publish their names. Regarding the real alleged crime of which Assange is suspected of involvement, the Russian newspapers tend to class Sweden as the organiser of a “political scandal” surrounding WikiLeaks, and “the insane setting for all diplomats around the world” (“Gromkoye”, 2012). The same image is also utilised in the Latvian media. Even in 2010, Diena newspaper was explaining that the “enemy” was “some Swedish women”, “warring feminists” whose names were then revealed along with facts about their work and family and their “obsession with humiliating a noble man” (“Asanžs un”, 2010). The word “rape” here is written in quotation marks and one of the women is described as a “sociopathic feminist” who “wanted to have sexual relations with one of the world’s most revered and sought-after men” (“Asanžs un”, 2010). There is no doubt here that hackers are heroes (fighting David’s battle against Goliath, which is represented as evil governments), and this also relates to the output of the Japan Times. The newspaper compares Assange to a data hacker in Latvia. “In Latvia, an artificial-intelligence researcher at the University of Latvia’s computer science department who earlier this year leaked confidential records on the income of bank managers has been praised as a modern “Robin Hood”, because otherwise the public would not have known how much some people were continuing to be paid while their banks were being bailed out with public funds”, wrote Peter Singer (“When does”, 2010).

Discussion and conclusion

- The analysis of all 890 newspaper articles proves that visualisation is a widespread phenomenon in today’s media values. This can be explained by the massive background of audio-visual culture or with efforts to simplify storytelling through the use of visual input.

- Visualisation uses myths that are rooted in each individual country’s habitus. Globalisation (via the internet) blurs the boundaries between countries and their journalistic fields and requires a more objective presentation of the medial message. This would prevent cultural conflicts between different journalistic fields, which is something that tends to simplify the message through visualisation and, due to this, collide with itself.

- Media uses the visual even when reporting on judicial processes. The Assange case shows that news reporting (through visualisation) is emotionally coloured and, as a result, non-objective or non-substantial.

- Julian Assange is a strong, challenging personality and his run through various trials in the UK is regarded by most of the world’s media (in a general sense) as a film or a video game, one in which the action itself seems fictional. This illusion is caused by visualisation.

Reference list:

Agar, M. (1994). Language Shock: The Culture of Conversation. New York: William Morrow and Company.

Amnesty oense om Assange-uttalande. (2012, September 28). Dagens Nyheter.

Assanges borgensmän uppmanas betala. (2012, October 08). Dagens Nyheter.

Asanžam piešķirta Serbijas Žurnālistu asociācijas Gada balva. (2011, May 02). Diena.

Asanžs kļuvis par izsmieklu! (2011, January 01). Diena.

Assanzh raskritikoval film o sebe v pisme Kamberbetchu. (2013, October 11). Gazeta. Ru

Asanžs un izvarošana. (2010, December 15). Diena.

A spotlight on the WikiLeaks organization. (2010, July 27). The Star Online.

Assange appoints WikiLeaks Party campaign director for Senate bid. (2013, April 02). The Malaysian Insider.

Assange embassy stand-off costs London police. (2013, February 16). The Star Online.

Assanzh, Dzhulian: Sozdatelj internet-resursa WikiLeaks. (2013, November 11). Lenta. Ru.

Assanzh. Generalny vopros po zakazu CRU? (2010, December, 08). RIA novosti.

Assanzh ne sobirayetsya pokidatj posolstvo iz-za problem so zdorovyem. (2014, August 18). RIA novosti.

Assanzh poobeshchal opublikovatj v 2013 godu novye dokumenty. (2012, December 13). RIA novosti.

Åklagare: Assange ska vara fortsatt häktad. (2014, February). Dagens Nyheter.

Ball, J. (2012, June 20). Julian Assange`s drama: in the third act, we still don’t know what the story is. The Guardian.

Bildt läckte information till USA.(2013. March 15). Svenska Dagbladet.

Bergström, B. (1998). Effektiv visuell kommunikation. Borås: Carlsson Bokförlag.

Borgström, Absurd idé om ambassadbyte. (2012, September 22). Dagens Nyheter.

Bourdieu, P. (2005). The Political Field, the Social Science Field, and the Journalistic Field. In Neveu, E., Benson R, (Eds) Bourdieu and the Journalistic Field. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Booth, R. (2012, October 9). Lady Gaga takes tea with Julian Assange. The Guardian.

Britanskiy sud reshil vydatj Dzhuliana Assanzha Shvetsii. (2011, February 24). Lenta. Ru.

Caso Assange: Hugo Chávez advirtió de una „fuerte respuesta” al Reino Unido. (2012, August 21).

El Comercio.

Carp, O. (2012, August 16). Assange får asyl i Ecuador. Dagens Nyheter.

Child, B. (2013, April 11). Oliver Stone meets Julian Assange and criticises new WikiLeaks films. The Guardian.

Dags för Sverige att avsluta fallet Assange. (2014, January 12). Svenska Dagbladet.

Dzhulian Assanzh ispugalsya smerti v amerikanskoy tyurme. (2012, December 24). Lenta. Ru.

Devetak, R. (2012). An introduction to international relations: the origins and changing agendas of a discipline. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ecuador skärper tonen om Assange. (2013, October 25). Dagens Nyheter.

Ekvador predostavil politicheskoye ubezhishche Dzhulianu Assanzhu. (2012, August 16). Novaya gazeta.

El Comercio. (2013, September 16). Julián Assange dialoga con periodistas y blogueros cubanos por Internet.

Elder, M. WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange’s TV show to be aired on Russian channel. (2012, January 25). The Guardian.

Fiske, J. (1998). Kommunikationsteorier. Borås: Wahlström & Widstrand.

Goodman, A. (2012, March 01). Stratfor, WikiLeaks and the Obama administration’s war against truth. The Guardian.

Greenslade, R. (2012, January 24). PCC rejects Assange complaint against New Statesman. 24.01. The Guardian.

Gromkoye delo. Sbezhal v kompjuter. (2012, August 20). Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Harding, L. The World Tomorrow: Julian Assange proves a useful idiot. (2012, April 17). The Guardian.

Hannerz, (1996). Transnational Connections. London: Routledge.

In Sweden, Julian Assange would receive justice. (2012, June 30). The Japan Times.

Julian Assange can stay in embassy for ‘centuries’, says Ecuador. (2012, August 23). The Guardian.

Julian Assange`s Australian Senate campaign to be led by anti-monarchist. (2013, April, 02). The Guardian.

Kritik mot dyr Assange-bevakning. (2013, November 07). Dagens Nyheter.

Kryphål i lagen chans för Assange. (2013, August 04). Dagens Nyheter.

Lagen måste ha sin gång. (2012, August 17). Dagens Nyheter.

L’Etang, J. (2006). Public Relations. Critical Debates and Contemporary Practice. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lull, J. (2006). Media. Communication, Culture. Cambridge: Polity Press.

McCracken, G. (1990). Culture and Consumption: New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Mediji: ASV sagatavojušas slepenas apsūdzības pret WikiLeaks dibinātāju. (2012, February 29). Diena.

Milne, S. (2012, August 21). Don`t lose sight of why the US is out to get Julian Assange. Ecuador is pressing for a deal that offers justice to Assange’s accusers – and essential protection for whistleblowers. The Guardian.

Mirzoeff, N. (2009). An Introduction to Visual Culture. London: Routledge.

Mitchell, W. (2007). Showing Seeing. A critique of visual culture. In Mirzoeff, N. (Eds). The Visual Culture Reader. London: Routledge.

Na kavo Assanzh pokinet Britaniyu? (2012, August 17). Novaya gazeta.

Obvinayushchiye Assanzha shvedki zayavili o podderzhke Wikileaks. (2010, December 25). Panorama Ru.

Pilger, J. (2013, February 14). Assange hate is the real cult. The Guardian.

Please-Take-Assange-to-Stockholm syndrome. It’s the diplomat’s disease. (2013, February 08). The Guardian.

Oxford students to protest at Assange ‘visit’. (2013, January 10). The Guardian.

Quinn, B. (2013, March 30) Ecuador raises Julian Assange case with Labour. The Guardian.

Sexual politics and the veneer of free speech. (2010, December 26). The Japan Times.

Sverige ger Assange skäl att le i ambassadens spegel. (2012, August 26). Dagens Nyheter.

The cultural contradictions of Europe’s multiculturalism. (2011, March 02). The Japan Times.

Thompson, J. (1990). Ideology and Modern Culture. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Thompson, J. (1995). The Media and Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Townsend, M. (2012, December 03). Julian Assange faces renewed arrest attempt over sex offence allegations. The Guardian.

Tupik vmesto shturma. (2013, August 17). Gazeta.Ru.

Unasur respalda a Ecuador por asilo a Julian Assange en embajada en Londres. (2012, August, 19). El Comercio.

Unasur y ALBA se reunirán el fin de semana para tratar caso de Assange. (2012, August 16). El Comercio.

Waiting for the WikiLeak dam to break. (2011, January 25). The Japan Times.

Velikiy i uzhasnyy. (2010, December 06). Kommersant. Ru.

When does transparency start eating its tail? (2010, August 17). The Japan Times.

Why is Julian Assange trademarking his name? (2011, March 01). The Guardian.

Why U.S. government is afraid of itself. (2013, July 20). The Japan Times.

WikiLeaks’ Assange fears US, says will stay in embassy. (2013, June 19). The Star Online.

WikiLeaks dibinātājs vadīs jaunu televīzijas raidījumu par pasaules nākotni. (2012, January 24). Diena.

Wikileaks founder Assange seeks Ecuador asylum. (2012, June 10). Mysarawak.

WikiLeaks founder is jailed in Britain in sex case. (2010, December 08). The Star Online.

WikiLeaks Party unveils Australia election plans. (2013, April 07). The Japan Times.

Wikileaks: Swedish minister says Ecuador living in ‘fantasy world’. (2012, August 17). The Telegraph.

Zalech na dno v Kito. (2012, August 16). Gazeta.Ru.

Sandra Veinberg, PhD, Associate Professor of Communication Sciences at RISEBA. Previous workplaces: the Universities of Latvia, Moscow and Stockholm. She is also the author of the monographs The Mission of the Media (2010), Public Relations or PR (2007), and Mass Media (2008), all of which were written in Latvian, and Censorship – The Mission of the Media (2010), a collection of scientific essays written in English.